Apoteka – Space for Contemporary Art

Trgovačka 20, 52215 Vodnjan / Dignano

curated by Branka Stipančić

text by Sabina Softić

7 September – 12 October 2024

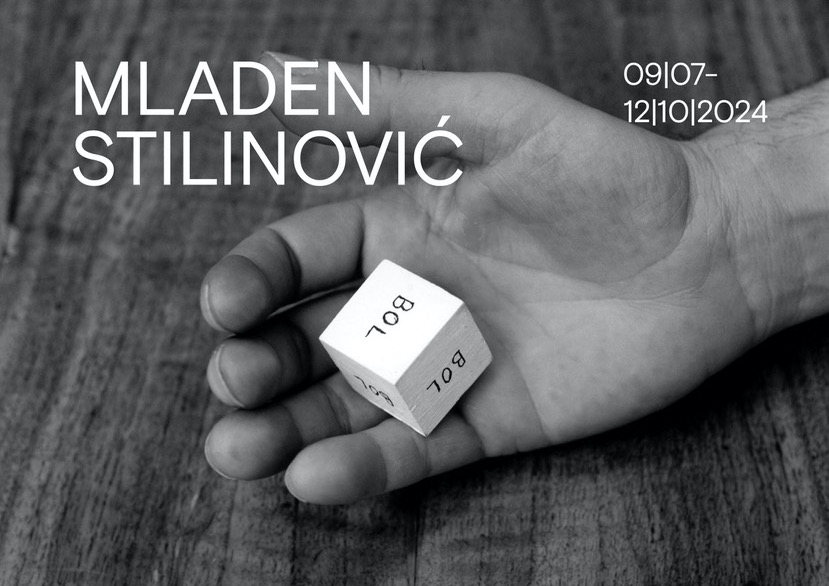

Mladen Stilinović, Igra bol / The Pain Game, 1977

The Croatian language standard differs between pain (bol) in masculine and in feminine grammatic gender. In masculine it refers to a sensation of physical pain and suffering, and in feminine a sense of spiritual pain and suffering. Although more than ten years have passed since then, I still remember when our morphology teacher taught us this distinction and my instinctive wonder about it. Back then, still timid and young, my questioning of authorities was quiet, but it marked the onset of my personal relationship and understanding of the ideological background of language. A few years later I met Stile as he braved the pain (masculine), and by immersing myself into his work, library and space, I started becoming acquainted with his experience of pain (feminine).

Albeit present in Mladen’s earliest works (his poetry and experimental film), he explicitly opens the topic of pain in the seventies with the piece The Game of Pain. On each of the six fields of a white dice he handwrites pain and calls for a seven-minute game with one’s own patience, reconciliation with the inevitable and equal outcome at every roll of the dice. He continues to deal with the theme in artist’s booklets in which he writes days of the week on the pages or numbers which he all then equals to pain. He crowns this process by ‘revising’ the Oxford English Dictionary (Dictionary – Pain, 2003) in which on 523 pages he covers the meaning of each word in white, creating an absence he then substitutes with the word pain. Because as Stile says himself, by repeating you don’t just practice to repeat, you also practice to forget.[1]

Thinking about pain, he saw his intimate experience of it, and of silence, absence and solitude, in the color white. In the nineties, while coping with a particular experience of numbing pain and helplessness, he produced a series of white works in which he covered everyday objects in white paint, the color of the walls which makes things invisible despite their presence. He covered the space in white papers to create an absence of information. He focused on zeros to which he added and subtracted zeros. He multiplied and divided nothing to reduce it to its essence – immateriality. Silence. Pain.

And the starting point of pain? The fundamental conflict is ideological. Linguistic. The beginning of the experience – the chicken or the egg, paper or money, it all begins with language. You learned the concept of ‘pain’ when you learned language, said L. Wittgenstein, but Pain is not in the language. Language inflicts pain.[2] Having to exist inside a limited system creates a rudimentary feeling of hopelessness and helplessness. Stile wraps a stone in paper with a written verse from a poem by Mandelstam interweaving heaviness and lightness. The poet’s it’s easier to lift a stone then to say your name reminds a bit of the dichotomy in language and makes you wonder which powerlessness is more difficult – the one that doesn’t make freedom of spirit and thought possible or the one limiting the freedom of movement?

Branka Stipančić curates in Vodnjan’s Apoteka a small ‘edition’ of Mladen’s pain. On the shelves she places books: My Sweet Little Lamb, Subtracting Zeroes, I have no time. Above the shelves she places Stile’s photo series and books, his representative Artist at Work and The Foot – Bread Relationship. In the drawers that once used to safekeep medications she stores the fragments of Stile’s thoughts, ideas and quotes he loved, with the intention of almost making us hear his voice from within. In the first room she confronts us with powerlessness every step of the way, it is clearly before our eyes, but also hidden in small, irregular corners. Audience becomes a participant, if, of course, they dare to do so, because who knows what might be revealed when a person embarks on the quest of opening the drawers of pain? The process is additionally exalted by mirrors which give us a chance to face ourselves in that exploration. Going deeper into the space, we get a chance for a brief pause before entering the last room, where we are confronted and surrounded by the cruelty of pain. Although we find ourselves in a similar reading process as it was with the booklet I have no time, here Dictionary – Pain leaves us with extra space for an intimate experience and reconsideration of our own relationship with pain.

With the exhibition Mladen Stilinović – Pain, Branka poetically connects spaces of pain. The space of the former pharmacy, although strongly marked by the concept of pain, also represents a small shelter from it. It tries to offer solutions. A similar procedure can also be seen in Stile’s work, an opulent intersection of philosophical thought, poetic heritage and his intimate experience which binds and shapes all these segments together. By understanding the essence of the human experience and its powerlessness, he doesn’t oppose pain aggressively, too aware of the absurdity of such a fight. He accepts the hopelessness of the human experience and devotes himself to its antithesis which is not comfort, pleasure or ease. The antithesis to pain is freedom, the ideal of the human spirit devoid of the cold and iron systematism of grammar, terminology and definitions. Of value and market. Of purpose.

Sabina Softić

[1] Stilinović, M.: O moći, bolu i… (1995)

[2] Ibid.

Photos: Matija Debeljuh, Branka Stipančić

Mladen Stilinović – Pain

“When I say pain, there are immediately questions: What kind of pain, whose pain, where is it from, as if pain must be explained, analyzed. There is nothing to explain… pain is here.”

This is one of Mladen Stilinović’s artistic statements on the meaning of pain. For him, pain is—among other things—a manifestation of the ideology of language. Language, however, is faulty because by the very processes of naming and rhetorical repetition it ultimately becomes devoid of meaning. It can be fragmented, reduced to nothing. Stilinović’s work relies on Wittgenstein’s concept of language, but also expands it; to Wittgenstein’s assertion that you learned the concept ‘pain’ when you learned language, he adds the recognition of both pain and the language of pain. Language, he says, causes pain.

The multifaceted nature of pain—as language, sensation, social symptom, helplessness, negation, and acoustic sign—is Stilinović’s frequent topic. The recent show at the Vodnjan’s Apoteka – a space for contemporary art, explores these perspectives.

The show is curated by art historian Branka Stipančić, the artist’s wife and undoubtedly the foremost authority on his work. Beyond her outstanding professional credentials, Stipančić brings a profound understanding of Stilinović’s creative and intellectual processes, along with a deep emotional investment. This emotional component is embedded in the Vodnjan show as a meta-code and flows into that elusive excess inherent to art – a very special atmosphere of the exhibition, or an intangible allure.

In the intimate Vodnjan gallery, originally a pharmacy (where the pharmacy cabinet of drawers still dominates the entrance exhibition space), Branka Stipančić presents the exhibition Pain. A pharmacy, as Sabina Softić reminds us in the catalog, stands both for pain and a “small refuge from it” – a space of simultaneous affirmation and negation. This duality also characterizes the artist’s work with language, language itself being the beginning of everything.

In front of the pharmacy, an unfolded cube is drawn with chalk on the pavement, as in the children’s game of hopscotch, with the word Bol (pain) inscribed in each square. On closer inspection, we notice tiny wings attached to the squares that would allow the flat drawing to be easily reassembled into a three-dimensional cube. The open cube evokes the ‘pre-poetry’ of Vlado Martek, Stilinović’s fellow artist and close friend, and might almost be seen as a subtle invitation to the exhibition.

Across the three gallery rooms, Branka Stipančić sets out Stilinović’s work, adapting the existing space to his concepts. The first room, with the built-in pharmacy cabinet, is site-specific: a space of pain and healing unfolds through the language of pain. The central work is Igra Bol (The Pain Game), where Stilinović has hand-written the word Bol (pain) on each of the six sides of the cube. The game lasts seven minutes, and the outcome is inevitable – will rolling the dice eliminate chance when nothing exists but pain? Beyond pain, nothing.

The theme of ‘nothing’ recurs and multiplies in the small-format artist’s book, where zeros are deducted from and added to zeros across its pages. On the notice board on the wall, white slips of paper represent the absence of information and language, silence, pain. In one of the booklets, the days of the week are equated with the word pain: Monday—Pain, Tuesday—Pain, Wednesday—Pain, and so on.

Also on display is the booklet Janje moje malo (Sve što vidimo moglo bi biti i drugačije) (My little lamb /Everything we see could be different), which serves as a guide to Stilinović’s intricate creative process, rooted in Wittgenstein’s theory of language games. The question of whether the drawn piglet becomes a lamb simply by naming it so through language addresses the complex relationship between reality and the symbolic code systems we use when trying to interpret it. Nothing is necessarily as we see or name it, because at the crossroads of communication, different language codes often clash rather than cooperate.

Alongside these, there are other booklets, such as Nemam vremena (I Have No Time) or Umjetnik radi (Artist at Work). The latter, in leporello format, features the artist in bed, sleeping, but if Wittgenstein’s theory is applied, he may in fact be thinking. The booklet’s accordion-fold form is stretched across the pharmacy cabinet, compressing and spilling over the notions of work, sleep, illness, healing, pain…

Another curatorial approach worth noting involves the original pharmacy drawers, where medicines were once stored – complete with handwritten labels detailing the drug’s name and dosage – which are used by Stipančić to store slips of paper with quotes from Stilinović’s books or interviews, adding depth to the artist’s voice. Stilinović often printed verses and texts related to pain in his exhibition catalogs and by incorporating this into the exhibition/artistic space, Stipančić creates an archive of quotes, Stilinović’s thoughts and readings, providing a unique guide through the exhibition. Visitors are free to take the slips of paper, assembling their own personal archive of the artist’s reflections.

Some works are actually hidden in the drawers and cabinets, inviting viewers to explore. After all, it is the act of play – concealing and revealing meanings, ideologies and symbolic systems – that is at the very core of Stilinović’s output.

The second, transitional room is occupied by the manifesto Pohvala lijenosti (The Praise of Laziness), Stilinović’s defining statement on artistic output within the context of art as a product of geopolitical and economic power structures. The manifesto is pivotal, and the forces it outlines are echoed throughout his work. It also functions as a Brechtian pause in the structure of the exhibition – an interlude before the final, radical, visceral confrontation with pain in the final room and the work Dictionary—Pain.

In Dictionary – Pain, Stilinović transforms an English dictionary covering the pages in whiteout and leaving only alphabetically ordered words to each of which he assigns a single meaning: pain. The English language is a language of power, and Stilinović reduces it to pain. Everything is pain. In a 2003 interview with curator Tihomir Milovac, excerpts of which are in the cabinet drawers, Stilinović says: “In my dictionary, in a way I seek to cancel such ideological signs. I want to cancel them through an emotional, not rational, gesture, so that all the words in the dictionary are connected to pain. I simply covered the meanings of the words in white and in their place put the word Pain. For me, pain is the opposite of power; in fact, power produces pain, pain is a consequence of power.”

Pain is a universal human experience, yet—as Wittgenstein might argue—uniquely individual. It is both emotion and physical suffering. In Croatian language, pain as emotion is grammatically of feminine gender, while the physical pain is masculine. Sabina Softić, the author of the exhibition’s preface, uses this linguistic distinction to draw attention to the ideological foundation of language. The exhibition in Vodnjan seems to be of feminine gender, speaking to us gently and patiently, with humor, serenity and pain. These concepts, incompatible with rigid ideologies, are mutually inclusive ways of building spaces of resistance—in life, and especially in art, where dealing with different language systems is the basis of its complexity. In doing so, all possibilities coexist equally, opening, activating, and negating fields of meaning.

Irena Bekić

The exhibition review was broadcasted in Croatian, on Triptih broadcast, November 5th 2024, HR 3 Station (HRT – Croatian Radiotelevision)

Translated into English by Maja Šoljan